Alewife Population Is Booming Again in Lake Michigan

This written report was originally published on December. nine, 2014. It is a part of the series "A Watershed Moment."

Some associated videos, graphics, photos and articles are bachelor simply in our archives. To read more, visit jsonline.com/greatlakes

Linwood, Mich. — Ernie Plant's eyes get broad when he talks nigh how spectacular Lake Huron's salmon fishing was dorsum in the tardily 1980s, when his dad would have him up due north on Fri nights after his high school football games.

They'd spend autumn weekends along the shore of the lake chasing the chinook that were chasing the alewives that ran so thick they even teemed in water-filled ditches along coastal roadways.

"Nosotros never had a boat," said the sales manager at Frank's Groovy Outdoors, a gear and bait shop n of Bay City. "But we didn't need one."

When Lake Huron's salmon crashed a decade ago, Plant, who holds a degree in biology from Northern Michigan Academy, had no doubt the lake would eventually right itself and the fish would come back.

And fish did return — but they weren't the fish Plant or many others expected.

What has happened in the decade since the crash of Lake Huron'southward two ascendant species — invasive Atlantic alewives and the giant Pacific salmon planted to gobble them up — is a remarkable story of nature's resilience. Efforts by lake managers to sustain the invasive alewives to keep the salmon fishing rolling had, for decades, pushed native species to the fringes.

Merely when the alewife dwindled and the salmon followed, there was an almost instant surge in native lake trout, walleye, smallmouth bass, chubs and emerald shiners.

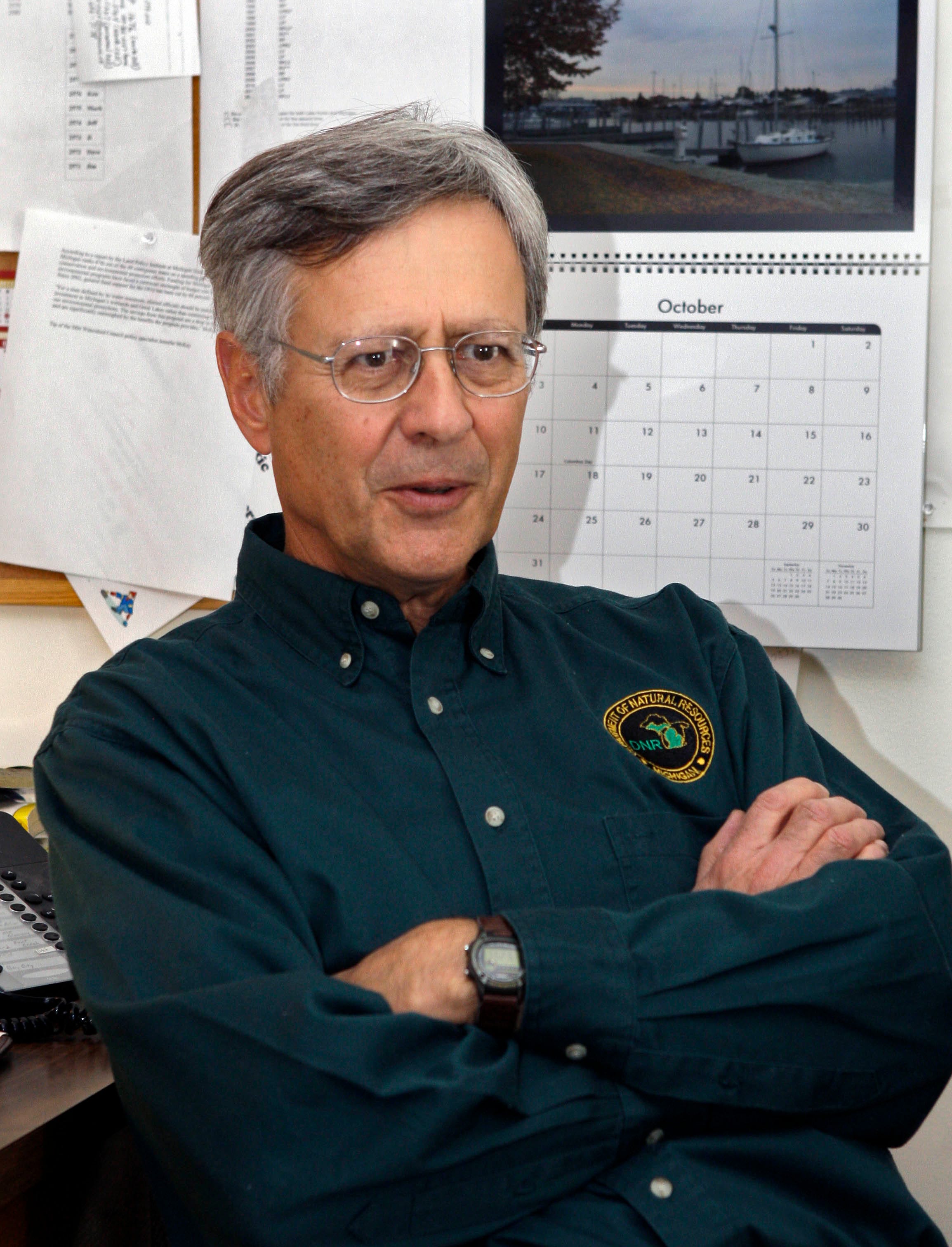

"Information technology all happened as presently as the alewives were gone," said Michigan Department of Natural Resources biologist Dave Fielder. "The natives started producing like crazy."

The remarkable result is that today the top of the Lake Huron food chain more than closely resembles its natural self than anytime since the lamprey and alewives invaded in the mid-1900s.

"Lake Huron'southward fishery," said Jim Johnson, a retired biologist with the Michigan DNR, "is more stable and robust in the past four or 5 years than it has been in a long time."

Information technology has everything to do with the disappearance of alewives, and piffling to do with Howard Tanner and Wayne Tody'due south thousand salmon plan, crafted after alewives had over-run Lakes Michigan and Huron. Tanner said he was never interested in trying to bring dorsum native species just considering they were native. He wanted the best sport fishery he could way from the lakes — and for him that meant Pacific salmon.

And that led to managing the lakes in a manner that would preserve the invasive alewives for the salmon to eat.

Walleye

PAUL A. SMITH

- History:

Walleye, a pop sport fish, are native to the Great Lakes and are the largest member of the perch family. - Diet:

Juvenile walleye rely on zooplankton, insects and other small fish. Adults feed on larger forage fish. - Restoration:

Walleye have already been declared "recovered" on Lake Huron's Saginaw Bay, where they have hitting tape numbers even though the stocking programme ended in 2006.

"You lot wanted the alewife to be alive and healthy. You wanted them at that place forever," said Tanner. "Mayhap not every bit such a large nuisance, just that was the foundation of what you were trying to build. We didn't want to destroy information technology."

Some biologists on Lake Huron today are looking at alewives completely differently.

I of them is Fielder, who proudly displays on his cluttered desk a framed "Tanner and Tody Award" received from the state for examining what'due south happened to Lake Huron's nutrient chain since the alewife plummet.

His conclusion:

"If you really want a native fish recovery, yous're not going to fully achieve that in the presence of alewives, unless natives are sustained by hatcheries," said Fielder. "And how can you call that a recovered fishery?"

Biologists had long suspected that the massive schools of alewives were trouble for native species; they just didn't know how much trouble until the alewives nigh disappeared on Lake Huron. It turns out alewives are death for the Swell Lakes' native fish species in a number of ways. They gobble upwardly the eggs and young of native species and out-compete them for the zooplankton that is the foundation of the lake's nutrient concatenation.

But alewives as well doom lake trout in a fashion that borders on subterfuge. Alewives carry high levels of an enzyme that triggers a thiamine deficiency in trout, which causes their eggs to either non hatch or induces deadly development issues in trout offspring.

The thiamine problem has been known for years, but the extent that information technology was foiling federal efforts to restore lake trout in the Corking Lakes was non grasped until the Lake Huron plummet.

The meridian native predator had been sustained on Lake Huron with hatchery plantings for decades. But since the alewife declines, the trout are over again successfully breeding in the wild. Lake managers are considering stopping that hatchery plan — something most biologists would have idea improbable just six or seven years agone.

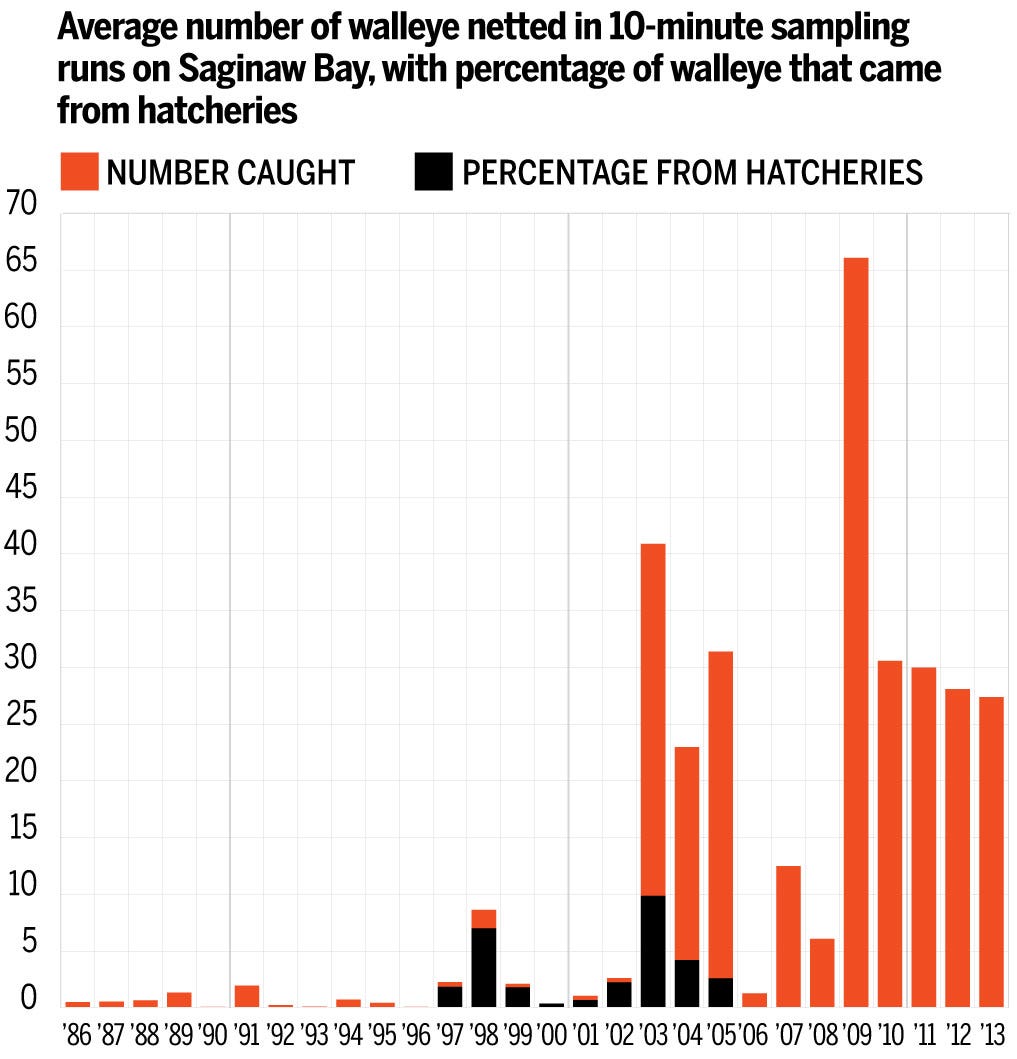

Walleye have already been declared "recovered" on Saginaw Bay, an inlet on the western side of Lake Huron that spans more than ane,000 square miles and was the nutrient-rich incubator for much of the lake's alewife population. Walleye have hit tape numbers in the bay even though the walleye stocking programme stopped in 2006.

"If an alewife swam into Saginaw Bay, it would have a half-life measured in minutes. I'thou serious," said Johnson. "The walleye will just kill them."

It'southward as if the lake's own allowed arrangement is restoring itself.

SOURCE: GREAT LAKES FISHERY Commission

For years after the alewife invasion, the walleye fishery on Lake Huron'southward Saginaw Bay was sustained only past hatchery-raised fish. Only When the alewife population collapsed, native walleye started reproducing in the wild. Walleye numbers have reached record levels even though the stocking program has been stopped.

This ascension of the natives is, ironically, tied to the moving ridge later on wave of invasive species that made their style into the lakes in the decades after the lamprey and alewife infestations.

Outset came the zebra mussel, carried in by overseas freighters sailing up the St. Lawrence Seaway. And then came its cousin, the quagga mussel. Then came an infestation of a picayune bug-eyed fish called the round goby, which made its style into the lakes the aforementioned style equally the mussels, and from the same place — the Caspian Sea basin.

The fiddling goby has become the blight of lakeshore recreational anglers because the fish feast on smallmouth bass eggs and out-compete native species for food. They likewise are quick enough to nibble the worm off a claw without its owner knowing. Or, worse, they latch on with a tug, and take to be reeled to the surface, stripped from the hook and discarded. Over and over and over.

Yet gobies take emerged as precious in one critical style. Unlike most fish now in the Great Lakes, gobies — with their tooth-like teeth — can crack the shells of mussels and gobble upward their piffling bundles of meat. This opens up what would otherwise be a nutritional dead end. Gobies swallow mussels. Bigger fish swallow gobies.

"Lots of fish eat them," said Jim Baker, a Bay Metropolis-based biologist with the Michigan DNR. "They are the right size and there are lots of them. They are about the only fashion that, in a large way, the energy tied up in mussels gets dorsum into the predator fish."

Whitefish

Mark HOFFMAN

- History:

While these Slap-up Lakes natives remain plentiful in certain parts of the lakes, whitefish populations were affected past the invasion of ocean lamprey and commercial over-fishing. - Nutrition:

The invasion of quagga and zebra mussels had a significant bear on on a tiny shrimp-like organism that was the preferred food source for whitefish. Whitefish have since adjusted and are now feeding on mussel-eating gobies.

That includes lake trout, walleye and smallmouth bass. It fifty-fifty includes whitefish, which did not evolve equally a fish eater in the Not bad Lakes. Only since the whitefish's preferred food source, a shrimp-like organism, disappeared with the inflow of the invasive mussels, they have turned to gobies, even if they must rip their cheeks to get their jaws effectually them.

Lake trout are showing a similar tenacity.

"Nosotros catch lake trout with their noses all banged upwardly," said Baker, "because they've been digging gobies out of the rocks."

Chinook have demonstrated no such resilience. They are built to banquet on schooling fish high up in open waters — fish like alewives — and so far they have non learned how to grub out a living on the lake bottom along with the native predators.

"Those species that can make the switch to gobies are OK," said Fielder, a fellow Michigan state biologist. "Those that couldn't, they're gone. And the chinook couldn't."

The chinook collapse has not come up without financial consequences. Economic data shows the top angling towns along Michigan's due east coast have lost, collectively, a minimum of $19 million per year since the collapse. It is reflected in empty marinas and hotels, airtight allurement shops and solitary harbors.

But that does not mean the fishing is bad.

"Lake Huron does not deserve a reputation for poor angling," said Fielder. "Information technology'southward just not the familiar chinook salmon fishing experience."

Information technology has taken several years, but some local economies are hitching themselves to the recovery of native species, especially effectually Saginaw Bay.

"A lot more people fish for walleye than chinook," said Plant, the outdoor store sales director. "It's more economical. The equipment costs less and the boats don't have to be so big because you don't have to leave so far."

Asked whether he'd welcome a return of the alewives and salmon of his memories, Plant paused and looked upwards at the ceiling of the sprawling bait and gear shop, packed on a Tuesday morning with fishing poles, high-tech sonar fish finders — and customers.

"I don't know," he said after taking a deep breath. "Nosotros've adapted."

On a chilly autumn morning, Wisconsin'south chinook salmon factory was thrumming along about the Lake Michigan shoreline.Thump. Whoosh. Phst. Squirt. Stir. Bam.

At the caput of Strawberry Creek nearly Sturgeon Bay, the production line started in a man-made puddle swarming with hatchery-raised chinook.

These adult fish had spent their youth at a hatchery in fall 2011 and were and then planted into a concrete pond at Strawberry Creek in spring 2012 for several weeks then the scent of "home waters" could be imprinted on their olfactory arrangement. Then the gates to the pool were opened and the cigarette-sized fingerlings flitted for the open waters of Lake Michigan.

2 and a half years later on, these now log-size beasts have followed their noses toward the Lake Michigan coast, into the man-made Sturgeon Bay Canal, up Strawberry Creek and right into the behemothic concrete pond of their youth.

Here, on the last day of their lives, a crane scooped them from the puddle in writhing clusters. They were dumped into a tub bubbles with a numbing gas and then, one by one, fed down a chute.

Thump — The hammer on the SI five M3 Stun Motorcar delivers a knockout blow to the skull and out the back of the contraption comes a limp chinook, eye cocked toward the clouds with all the life of a push.

Whoosh — Rubber-gloved fishery workers slide the carcass onto a scale where it is weighed, measured for length and identified as male person or female.

Phst — Females have their stomachs popped with the needle from a hose hooked to a carbon dioxide tank and are gassed up until their bellies excrete a stream of bright orange eggs into a bucket — well-nigh v,000 per fish.

Squirt — Males are bent and squeezed by an assembly line worker in a manner that shoots their milt into picayune plastic cups with dart-throwing precision.

Stir — A gloveless technician dumps a cup of milt into a 3-gallon bucket containing the eggs from ii females, and then dips his fingers, sterilized by iodine, into the icy batter and swirls until information technology foams.

Bam — 10,000 eggs are fertilized.

The crop of before long-to-be-fish — more 200,000 on this 24-hour interval lone — is then taken by van to a state hatchery where the eggs will hatch in almost six weeks. The picayune fish volition feast briefly on nutrients in their egg sacs and exist gobbling hatchery pellets by January.

Come April they will accept grown to nearly four inches and will be brought back to the concrete pool at Strawberry Creek for a few weeks of acclimation before the gates open up and they jerk along with the electric current toward Lake Michigan, where they will chase the lake'south diminishing alewife population until they render to their concrete box in 2017. Or that'south the plan.

Biologists are bracing for an alewife plummet on Lake Michigan like to what happened on Lake Huron, though this is far from a certain thing.

While Lakes Michigan and Huron are actually two lobes of one behemothic body of water, connected by the Straits of Mackinac, they are in many ways distinct. Lake Michigan is a more "productive" lake due to the nutrients flowing from its tributaries that yield more alewife-sustaining plankton. The lakes also differ in water chemistry, temperature, depth and spawning habitat.

And while Lake Michigan also is now dwelling to a naturally reproducing chinook population, these fish are not convenance to the same degree they were on Lake Huron before its salmon crash.

Even so, both lakes have been so ravaged by invasive mussels that biologists believe the alewife collapse on Lake Huron may be a harbinger for Lake Michigan. It'due south been a concern for the better part of a decade, but it's become a growing worry.

Lake-wide fishery surveys conducted in recent years show the number of alewives are now less than x% of what they were in the tardily 1990s. The surveys also testify older and larger alewives are disappearing, which is precisely what happened on Lake Huron just before its collapse, where the combination of too many salmon and as well little nutrient meant non enough alewives survived to adulthood.

"It's kind of scary, if you lot wait at what happened on Lake Huron," Nick Legler, Bully Lakes fishery biologist for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, said during a intermission on the final twenty-four hours of this fall's egg harvest at Strawberry Creek.

"That's why we reduced stocking, to endeavour to get the system back in remainder."

States adjoining Lake Michigan this leap will stock simply 1.7 meg chinook — nigh one-half what was stocked just ii years agone and well below the pinnacle of about 8 million in the tardily 1980s.

The federal government, meanwhile, has been stocking some 3 million lake trout annually in Lake Michigan every bit part of its native species restoration programme that dates to the mid-1960s.

That restoration effort sputtered for decades — until the alewife population started to fade. At present show has emerged that the lake trout are finally producing viable offspring. The first hint came a decade ago when underwater cameras revealed clusters of pinky-sized fish on a reef in the center of Lake Michigan.

But would they survive?

About 5 years ago, pocket-size numbers of larger trout appeared possessing all their fins — an indication of wild birth (hatchery-raised trout have a fin clipped). In the last twelvemonth, biologists say surveys indicate every bit many equally 50% of the lake trout netted in some areas of Lake Michigan are naturally reproducing.

Federal biologists point to the driblet in alewives — and a subsequent healthy ascension in thiamine levels in lake trout eggs.

It's no surprise state fisheries biologist fear a salmon plummet. Chinook are what recreational fishermen accept wanted — and anglers pay the country fishery managers' bills. Nearly $23 million of the Wisconsin DNR'south $25 million fisheries budget comes from fishing licenses and taxes on fishing-related products.

With evidence piling upwardly that what is good for native lake trout is bad for planted salmon, and vice versa, us and federal government are trying to strike a dicey balance.

"The thought is that you keep enough alewives so yous take a chinook fishery merely non so many that you don't accept natural lake trout reproduction. Well, that'due south a razor-thin line," said Dale Hanson, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. "I don't even know if it'southward possible."

It wasn't on Lake Huron.

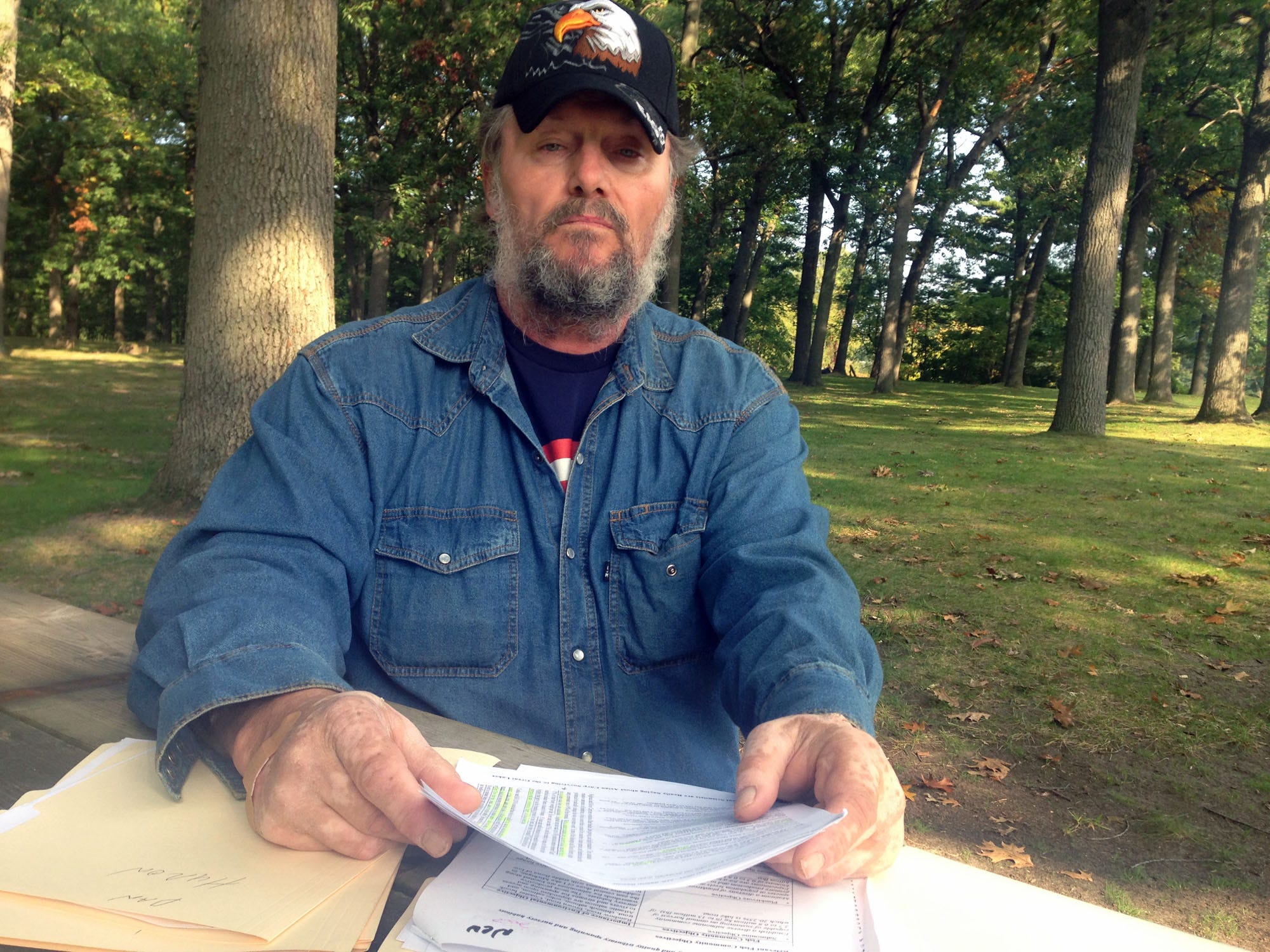

Tom Matych, a sixty-year-old retired crane maker from western Michigan, remembers how, as a kid in the 1960s, his nose could tell him when the native perch were running especially thick on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan well-nigh Muskegon at certain times of yr.

"If you could smell the paper mill, which smelled like rotten eggs, you knew the perch were coming, because the west wind blew in the zooplankton and the minnows, and the perch followed them in," he said. "I mean, people took those days off work."

Matych remembers how people rode the public bus with bamboo fishing poles, and how that passenger vehicle would finish at a allurement store about the lakeshore and how crowded the pier was and how he felt "10 anxiety tall" every bit a 5-year-old when he defenseless his first perch with his father.

It's an experience he wants to share with his ain young granddaughter, but Lake Michigan's perch fishery collapsed in the 1990s.

Yellow Perch

MARK HOFFMAN

- History:

Populations of this Great Lakes native were severely reduced following the invasion of the alewives in the 1950s. Their numbers on Lake Michigan rebounded past the 1980s, but then went into a steep decline. Commercial fishing for Lake Michigan perch in Wisconsin, except for the waters of Greenish Bay, was banned in the mid 1990s to try to revive the species, though numbers of adult fish remain extremely low. - Diet:

Immature perch begin feeding on zooplankton and lesser-habitation insects. Adult perch feed primarily on immature insects, larger invertebrates, and the eggs and immature of other fish.

Biologists arraign a circuitous set of factors, including a loss of perch-sustaining plankton tied to the quagga mussel invasion. Matych points a finger straight at their efforts to prop up alewives to protect the chinook fishery.

"I'grand not adept at existence politically correct," he said. "But when they say there is non enough food for perch, what they're really saying is there is not enough food for perch and alewives."

He cites the free energy — the number of little fish — it takes to make i big chinook.

"You need 123 pounds of alewives to make a 17-pound chinook, and you need 40 pounds of zooplankton to make 1 pound of alewives," he says. "That's a whole lot of zooplankton for one fish."

Matych is a pesky abet for a Lake Michigan perch stocking programme, something biologists say may exist fruitless, given the mussel-driven turn down in plankton and the number of stocked perch it would take for even a small fraction of them to survive long enough to exist caught.

But Matych isn't worried just well-nigh re-creating the perch fishery. He wants lake managers to change their focus from a system dominated past chinook to one that can sustain every bit many native predators as possible. He'southward non but thinking nearly more than species for fishermen to catch; he'south thinking about the ecological health of the lake itself.

Matych considers native predators to be the lake's "biotic resistance" to new invasions, noting that species like lake trout, perch, walleye and whitefish all feed on different things at dissimilar times in unlike places.

Big numbers of these fish, he maintains, brand the lake more resistant to new invaders such every bit Asian carp, which are currently held back from Lake Michigan by a leaky electrical bulwark on the Chicago canal organization.

Matych doesn't have a doctorate in fisheries biology. He doesn't accept any college degree at all. But he thinks big, like Howard Tanner.

"We want to do the same affair that Tanner did," he says. "But with native predators for the 180-something invasive species that the salmon don't eat."

That 180-plus figure for invasive species in the Great Lakes is actually a tally of all the lakes' non-native organisms, including the salmon that take been stocked. Only the gist of his argument is not lost on biologists.

"There is a trunk of show that says having a robust, co-evolved food web helps prevent invasive species' establishment," said John Dettmers, a biologist with the Great Lakes Fishery Committee. "It doesn't guarantee it, but it'south something to be considered by managers if they are concerned most invasive species."

Dettmers co-authored a 2012 newspaper that suggests a mail service-chinook Lake Michigan may be at manus.

"Fishery managers face up an interesting dilemma: whether to manage in the short term for a popular and economically important sport fishery, or to embrace ecosystem changes and manage primarily for native fish species that appear to be suited to ongoing ecosystem changes," Dettmers and his colleagues wrote.

The authors suggested numbers of native predators could exist boosted if lake managers close downwardly the salmon pump Tanner started on Apr 2, 1966. This could be accelerated, Dettmers and his co-authors wrote, past dosing Lake Michigan with so many chinook that they nearly eliminate the alewives which, in turn, could open up the door for a surge in native species.

"Maybe salmon was the correct medicine to apply 50 years ago," Dettmers said in an interview. "Merely perchance there are new treatments available at present — native fishes — to aid bolster the lake's immune system, if you will."

This tension over doing what'southward best for the long-term ecological stability of the lakes and what'southward fun for anglers and profitable for charter gunkhole operators draws into precipitous relief the dichotomy of Tanner's legacy.

Tanner is proud to have introduced salmon that created a spectacular recreational fishery, merely it'south articulate he is as gratified that he built a constituency for the lakes. The ecological health of the world's largest freshwater system, he maintains, is largely dependent on having fish in them that people want to catch.

Brown Trout

PAUL A. SMITH

- History:

While non native to North America, brown trout have been widely stocked across the continent for more than than a century. Great Lakes brown trout tend to stay near shore in waters less than 50 anxiety deep, which makes them an ideal gamefish for shallow bays. - Diet:

While non native to North America, brown trout take been widely stocked across the continent for more than than a century. Bully Lakes brown trout tend to stay virtually shore in waters less than fifty feet deep, which makes them an platonic gamefish for shallow bays.

The problem is he doesn't think the native species can practise that job. He is encouraged by the surge of naturally reproducing lake trout, just is dubious it will lure people onto the lakes.

"I've never been against lake trout," Tanner said. "I'one thousand just non very enthusiastic about lake trout. My ain feel is lake trout aren't a lot of fun to catch, and I incertitude if the charter boat captains can sustain a fishery on lake trout."

He calls trolling for walleye "about the near tiresome thing y'all can exercise."

"Like bringing in a moisture sock," he says.

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee biologist John Janssen has bristled confronting this chinook-first mentality during his own forty-year career on Lake Michigan.

He calls Tanner'southward thought to convert an alewife infestation into a popular and profitable salmon fishery a "brilliant" decision — for its time.

At present, he said, it's fourth dimension to view gobies in a similar manner — equally sustenance for the fish best suited for the ecological changes wrought by the recent circular of invasions. These species include natives like lake trout and walleye, as well as exotic brown trout, which have been stocked in the lake for more than a century but also are naturally reproducing in some tributaries.

To treat these sport fish as if they were a baneful species like carp, Janssen said, is to risk alienating a new generation of anglers — the very people who will be most motivated to value and protect the lakes in coming decades.

"There is nil bother nearly brownish trout," said Janssen, who grew up line-fishing for wild browns in western Michigan near the very waters where Tanner planted that beginning class of Pacific salmon. "Merely some of the chinook fishermen care for them as carp."

Janssen said this tension came to a caput at a recent meeting with lease gunkhole captains and other chinook boosters who railed confronting a plan to restore walleye along the Lake Michigan shoreline. Their fear was that it could put a dent in their chinook take hold of.

"The problem," the 66-year-old Janssen said, "is you guys are all old. I'g sometime. We're all going to exist dead pretty before long. The big result is the 12-year-one-time on the bicycle.

"What'south he going to be catching?"

A generation ago, Brian Settele was that 12-year-sometime, rolling his Schwinn 10-speed downward the Oak Leaf trail from Glendale to the Milwaukee harbor with line-fishing poles lashed to the handlebars.

His parents were going through a divorce and he institute sanctuary forth the Milwaukee waterfront, relishing his summer mornings by reeling in perch and the odd salmon that drifted into the harbor.

Today Settele is a licensed captain running charters out of McKinley Marina. He'll chase chinook if that's what the customer wants, or if they are actually bitter. He says there is nix like it.

"They will grab your line and pull it out a football field's length in a matter of seconds," he said. "The best way to explain what it feels like to have one on your line is to imagine continuing on an overpass of Highway 41 and having a car bumper down below grab your lure."

The thought that this cultural thrill could disappear has Tanner dismayed.

"Right now I'g very worried about Lake Michigan. It'southward on the same course as Lake Huron," he said. "The quagga is the culprit. There isn't any question about that. I'd hope for the demise of the quagga mussel, but I tin can't produce that demise, nor tin can anyone else."

Settele is learning to make a living despite the quagga infestation past focusing his business on brown and lake trout — two species that go along the clients rolling in.

One contempo customer was commencement-fourth dimension fisherman John Egan, age 8. His dad does not fish. Neither does his 75-year-old grandad, both of whom were along for the ride on a frigid, predawn Oct. 17.

The water was so blackness it was invisible equally Settele steered his gunkhole through the north gap of the harbor breakwall into the early morning swells. Non long after a flaming orange sun popped on the horizon, a reel whirred and Settele yelled for somebody to take hold of the bouncing rod.

John scurried up and snatched it. He felt the line tug somewhere deep below the greyness-light-green waves and began to crank the reel.

Y'all could see in the wrinkles of his nose and the creases effectually his eyes that he wasn't struggling so much as soaring. It'due south an expression he doesn't have when playing computer games or even chasing a soccer ball.

After a couple of grimacing minutes, his eyes popped and jaw dropped as a freckled 3-pound dark-brown trout broke the surface.

It might have been a scrawny thing when compared to ane of Tanner'due south Pacific beasts.

But information technology was John'southward fish, caught on John's lake.

And the hook was gear up.

About this project

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter Dan Egan investigated threats to the Slap-up Lakes and the effectiveness of government efforts to protect them during a nine-month O'Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism through the Diederich College of Communication at Marquette University.

Source: https://www.jsonline.com/in-depth/archives/2021/09/02/lake-huron-saw-revival-after-demise-alewives-and-salmon/7847622002/

Post a Comment for "Alewife Population Is Booming Again in Lake Michigan"