Did Whites Under 30 Back the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s'

In a series of three lectures last week, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Leon F. Litwack took in the sweep of the history of blacks in the American South

throughout the 20th century. His talks explored the legacies of Reconstruction and Jim Crow, the impact of World War II, and the promise of the Civil Rights Movement on black Americans.

Or, perhaps more accurately, according to Litwack, the failed promise of the Civil Rights Movement. In "Fight the Power," the final of his Nathan I. Huggins Lectures sponsored by the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research, the Department of African and African American Studies, and the Harvard University Press, Litwack led the audience from "We Shall Overcome" to today's angry, vengeful rap and hip-hop to illustrate how far America has come in leveling the playing field for blacks – and how far we have to go.

"At the dawn of the 21st century, it's a very different America, and it's a very familiar America," said the celebrated University of California, Berkeley, professor, his final lecture ending the series on a decidedly minor chord. "Everything has changed, but nothing has changed."

The promise of the movement

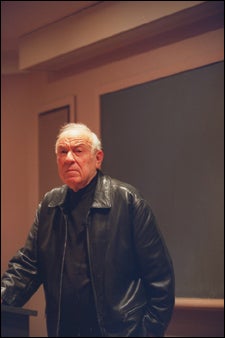

Litwack, who has taught at Berkeley since 1964 and has published several influential books on the history of blacks in America, appeared simultaneously august and hip, his bright white hair offset by a black turtleneck and leather jacket. And indeed, Litwack proved equally literate in the political and oral histories of the civil rights era and the obscenity-riddled rap lyrics of the 21st century ("I like rap music," he tells those who wonder who helps him research it).

The Civil Rights Movement, from its uprising in the 1950s through the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1965 and the turmoil of the late 1960s and early '70s, had a substantial impact on the lives and rights of American blacks, particularly those in the South, he said, citing dramatic changes at many of the South's most notable civil rights battlegrounds.

In Selma, Ala., for instance, when 600 civil rights activists marched in 1965, they were met with police brutality, tear gas, bullwhips, and clubs. Retracing the route of these earlier marchers 20 years later, 25,000 people, led by Coretta Scott King and Jesse Jackson, returned to Selma. Jackson received the keys to the city, and many of the sites the marchers passed had been proudly included on a city history tour.

Other hosts of civil rights struggles – Montgomery and Birmingham, Ala.; and the University of Mississippi, "Ole Miss," where integration was won with blood – boast of similar badges of civil rights success, said Litwack, and their pride is justified.

"To achieve these triumphs had not been easy," he said.

Litwack described how the civil rights cause was buoyed by a national mood and political agenda of freedom, one that feared its moral leadership against communism's threat would be undermined unless it considered black rights at home.

"The restructuring of race relations took on a new urgency, an importance reserved for matters of national security," said Litwack. "In the highest levels of government and much of the United States, white supremacy had become too costly to defend or to sustain."

He quoted President John F. Kennedy in a succinct summary of foreign policy's trickling down to civil rights: "Why can a communist eat at a lunch counter in Selma, Ala., when a black American cannot?"

Raising, betraying expectations

While legislation and civic leadership had a profound impact on the American South, however, racial practices and customs are not as easily altered as access to lunch counters, said Litwack. "The white South remained largely unmoved," he said, which only confirmed the suspicions of black Southerners. "Raising expectations, only to betray or defer them, had by this time become a very familiar theme to the black experience."

And, while the Civil Rights Act and the activism of black Americans produced measurable gains in the educational, professional, and political achievements of blacks, they have failed to deliver in far-reaching ways, claimed Litwack. In the early years following the passing of the Civil Rights Act, the rural South remained relatively unchanged in attitude, he said, and for many blacks who depended on whites for their livelihoods, the luxury of sharing a lunch counter or a water fountain with whites took a back seat to basic issues of survival.

"Even as the Civil Rights Movement struck down legal barriers, it failed to dismantle economic barriers," he said. "Even as it ended the violence of segregation, it failed to diminish the violence of poverty."

He cited school segregation as a victory of law but a disappointment in fact. The exodus of whites from cities to suburbs in the 1970s changed the struggle from keeping blacks out of public schools to keeping white students in. By 2000, more than 70 percent of African Americans attended schools in which they and other nonwhites were the majority, he said, and more than one-third attended schools where the enrollment is between 90 and 100 percent black.

Current statistics illustrate a yawning gap between black and white Americans in housing, health care, life expectancy, infant mortality, and income, Litwack continued. Unemployment among blacks is double that of whites, the poverty rate of black Americans is double the national rate, and 50 percent of the nation's prisoners are black.

"It all adds up to a rather grim chronicle of a people on the periphery, as the United States remains … in critical ways, two societies, separate, but unequal," he said.

From the Miracles to Outkast

Litwack, who opened his lecture with what he called an "overture" of the song "Fight the Power" by rap group Public Enemy, returned to music to illustrate the current generation of blacks' angry response to that "grim chronicle." In contrast to the sunny-sounding names of black groups of the 1950s and '60s -the Miracles, the Marvelettes, the Supremes – the turn of the 21st century has brought Niggers With Attitude, Public Enemy, and Outkast to the airwaves, their beats confrontational and their lyrics ringing with rage.

And, given the circumstances of many black Americans, it's no wonder, asserted Litwack.

"These are people who have articulated a growing despair," he suggested. "Some 30 years after the Civil Rights Movement, a new generation of Americans experiences rollback, backlash, and resentment."

Did Whites Under 30 Back the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s'

Source: https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2004/03/failed-promise-of-civil-rights-movement/

Post a Comment for "Did Whites Under 30 Back the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s'"